CAST: Kartik Aaryan, Kiara Advani, Gajraj Rao, Supriya Pathak Kapur, Shikha Talsania, Anooradha Patel, Siddharth Randeria, Rajpal Yadav

DIRECTOR: Sameer Vidwans

Satyaprem Ki Katha falls short of being a feminist film, despite its rare attempt in Hindi cinema to address issues like date rape and marital rape. It lacks the intellectual depth to fully grasp the values it claims to promote and lacks the sensitivity and commitment needed to effectively support them.

In contrast to Luv Ranjan’s Pyaar Ka Punchnama, which exhibited a strong disdain for women, Sameer Vidwans’ Satyaprem Ki Katha attempts to deliver messages about women’s agency while simultaneously depriving a woman of the ability to determine her own response to an assault. While films with a male savior complex are not uncommon, what sets this film apart is its strained and transparent attempt to conceal it.

The essence of the film, as conveyed through the lip-synced song “Gujju Pataka” performed by Aaryan during the opening credits, reveals the underlying theme: “Jo bhi mujhe karna hai karta hoon bol ke” (roughly translated as “I do whatever I want to, unapologetically”). These lyrics, despite being inconsistent with the overall characterization and narrative of the leading man, reflect the script’s most consistent quality of inconsistency. While these lyrics hardly align with the film’s overarching focus on women’s consent in sexual relationships, they are reminiscent of the aggressive masculinity often seen in films.

In a nutshell, Satyaprem Ki Katha oscillates between its dual objectives of supporting women’s rights and glorifying the male protagonist, even resorting to using lines that perpetuate aggressive masculinity, contradicting the film’s overall message.

Nevertheless, the film banks on Kartik Aaryan’s ability to deliver monologues a la Pyaar Ka Punchnama in its most Punchnama tone.

The overriding theme of the movie is consent.

Satyaprem, a disillusioned young man who failed his final Law exams, now assists his father Narayan (Gajraj Rao) in maintaining their household. Satyaprem’s sharp-tongued mother Diwali (Supriya Pathak) and sister Sejal (Shikha Talsania) do not contribute to domestic chores, and the house relies on the earnings of the women. Numerous jokes stem from this arrangement in the first half of the film. It appears to be a version of feminism that diminishes its essence: a film that claims to be progressive while finding humor in men performing household tasks. As if it were using humor as a shield to

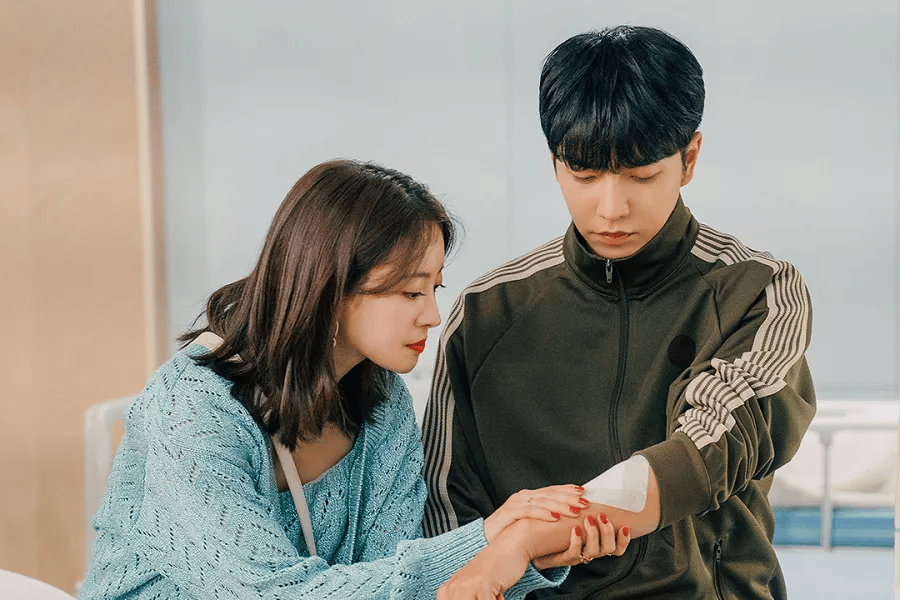

Satyaprem is in love with Katha, but she has feelings for someone else. Circumstances bring them together, leading both the film and Satyaprem to transition into warrior and savior roles.

Satyaprem Ki Katha revels in its loudness, from the grand sets of the song and dance sequences to the larger-than-life characters, emotions, and messianic fervor.

I mean what is that with a son-in-law screaming that his wife is asexual to his father-in-law in the middle of throngs of people in his savories store? Every stance taken is accentuated with the boldest strokes possible. Interestingly, just when the storyline appears to veer off course entirely, the writing manages to create a genuine chemistry between the main couple and introduces unexpected moments of tenderness. However, just as that tenderness begins to take hold, melodrama forcefully makes its entrance.

Rao, Pathak Kapur, and Advani excel in their roles, delving deep into the film’s most well-written scenes. Their performances outshine Aaryan’s limited acting range, overpowering him whenever they appear together on screen. While they bring depth and nuance to their characters, Aaryan relies on his limited repertoire of just two expressions.

In a rather problematic sequence of Satyaprem Ki Katha, an elderly man convinces his son to visit a young woman who is alone at home and confess his love to her. While the intention may seem innocent enough, the son, who is portrayed as a nice guy, interprets his father’s advice as an invitation to trespass by climbing over the compound wall and breaking into her house. All of this occurs in a film that supposedly explores the concept of consent. To preemptively address criticism of this scene, it is revealed that the woman actually requires medical attention, and the man’s intrusive behavior ends up saving her life.

In the most infuriating part of the film, a man disregards a survivor’s wishes and publicly discloses her rape at a social gathering, believing that she should not be ashamed. While it is true that she has nothing to be ashamed of, it should be up to her to decide whom she wants to confide in, and when and where she wants to share her story. Once again, the script tries to pre-empt criticism by portraying the woman as empowered by the man’s actions.

The highly debated remix of “Pasoori Nu” in the soundtrack of Satyaprem Ki Katha falls short compared to the original rendition from Coke Studio Pakistan, sung by Ali Sethi and Shae Gill.

The flaws, both minor and major, in this narrative, including Advani’s standout moments, are overshadowed by the writer’s apparent belief that it is acceptable for a man to persistently pressure a woman under the guise of being a supportive ally. At one point, Satyaprem tells Katha, “If the hero doesn’t save the heroine, then how will he become a hero?” However, much later, he acknowledges that he has imposed his own perspective of what is best for her. Regrettably, the film promptly reverts to doing exactly that.

Why cannot scriptwriters think more?